If someone were to claim they knew a story that involved the Holy Grail, a band of pirates, William Shakespeare, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Edgar Allan Poe, you might think the tale was a riddle or a fanciful movie script. However, one particular site in Canada holds a history that brings together all of these elements and more.

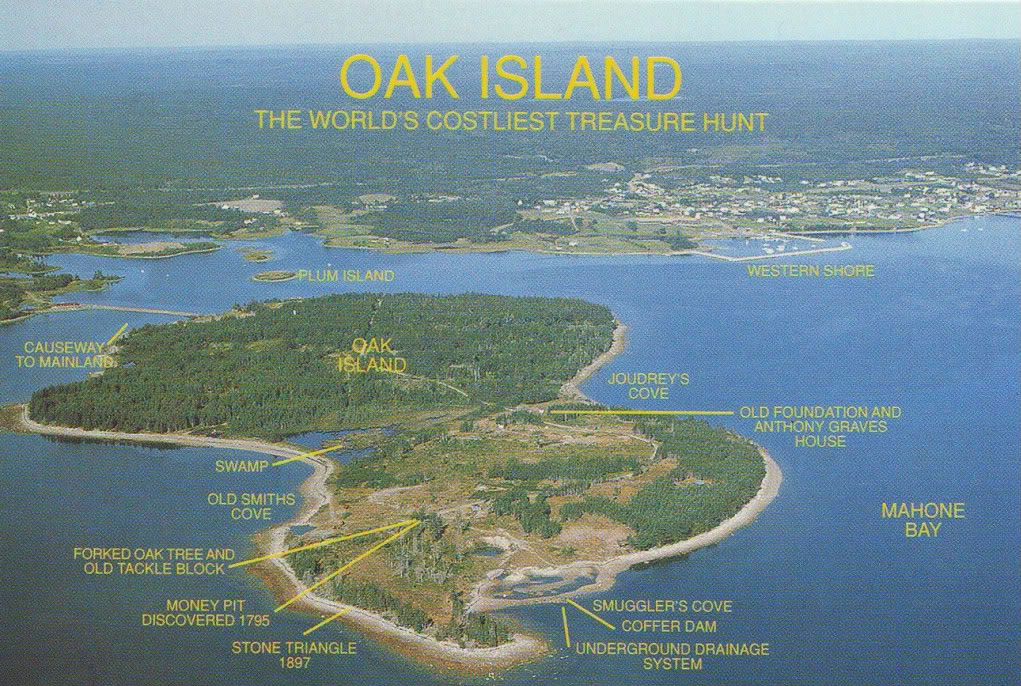

Located off the shores of Nova Scotia, along Canada's Atlantic coast, Oak Island is among approximately 360 islands dotting Mahone Bay. To the casual observer, the 140-acre island appears like many in this part of the province. Rocks and sand skirt the perimeter of the landmass while native forest and brush cover much of its interior. At first glance, the seemingly mundane island conceals any evidence of historical importance. However, appearances can be deceiving. Despite the natural scenery and serene setting of Oak Island, the story of this island's past is replete with mystery, intrigue and even tragedy. The potency of the story that follows has captured the human imagination and has driven men to their graves. From academics to adventurers, many have grappled with trying to explain the mystery, but none have been able to get to the bottom of the Money Pit of Oak Island.

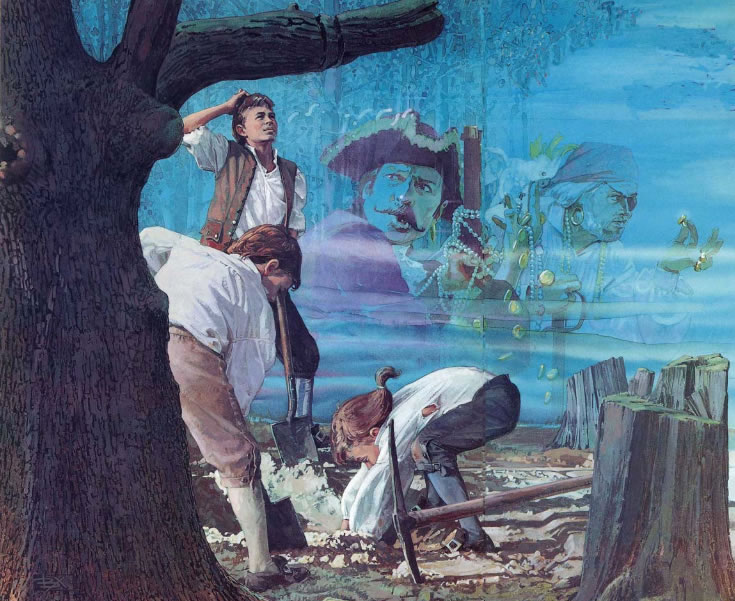

By most accounts, the story of Oak Island's Money Pit begins in the summer of 1795 when a teenager named Daniel McGinnis saw strange lights on an island offshore from his parent's house. According to author Lee Lamb, upon investigating the island for the source of the lights, McGinnis noticed a peculiar circular depression approximately 13 feet in diameter on the island's forest floor (2006). Looking around, McGinnis observed that a number of oak trees surrounding the depression had been removed. In addition, McGinnis saw that a block and tackle hung from a severed tree limb directly over the shallow hole. Although some researchers refute the presence of the block and tackle, whatever he witnessed that day convinced him that the scene was worth investigating. McGinnis decided to leave the island to enlist the help of two friends, John Smith and Anthony Vaughan. The following day the three teenage boys began enthusiastically excavating the curious site.

One of the reasons McGinnis, Smith and Vaughan were so excited to investigate a dirt depression on an otherwise nondescript island in eastern Canada can be found in an enticing chapter in Nova Scotia's history. As described by the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, the "Golden Age of Piracy" occurred between 1690 and 1730. At this time, Nova Scotia had only a few European settlements. With just over 200 nautical miles separating the remote bays of present-day Nova Scotia from the thriving commercial center of colonial Boston, pirates were known to frequent areas near Oak Island. The unpopulated wilderness of the region provided an abundance of natural resources to restock and repair vessels while its isolation proved an ideal place to harbor their vast misbegotten treasure. In fact, one notorious pirate, the infamous Captain William Kidd, admitted to burying an unspecified wealth of treasure in the area before his capture in 1699 (Conlin, 2007).

Along with many residents in the eastern province, the three boys digging on Oak Island must have been aware of the fabled pirates and had notions of gold doubloons in mind. It wasn't long before the young excavators came across buried evidence to further convince their imaginations. Two feet beneath the topsoil, McGinnis and his friends uncovered a layer of flagstone extending across the surface of the opening (Crooker, 1993). Excitedly, the boys pulled the rock floor away from the pit to retrieve the golden bounty that must be hidden below. Unfortunately for them, the boys only discovered more dirt. Undeterred, they continued their excavation. Any treasure worth finding would certainly require more than two feet of digging.

As the teenagers continued burrowing down, they followed the walls of the previous hole. In doing so, the boys found that the pit had narrowed to seven feet in diameter. They also noticed the work of their predecessors. Imprinted in the clay of the tunnel wall were the impressions of pickaxes. Had these marks been left by pirate laborers before securing their treasure underground? The adolescent explorers were determined to find out.

At a depth of ten feet, the boys discovered a layer composed of rotting wood timbers. The timbers spanned the width of the hole, forming a wooden platform. The ends of the timbers had been driven into the sides of the tunnel wall to firmly anchor the structure. This deliberate barrier and the hollow sound beneath the timbers must have confirmed to the boys that vast wealth was close at hand. The team eagerly continued their efforts, removing the timbers to claim their treasure. Just as before, the enthusiastic excavators were again disappointed. After taking out the barrier, the boys found a two-foot pocket of air followed by soil that had settled below (Lamb, 2006).

McGinnis and his friends carried on undeterred. Tunneling down to approximately 20 feet, the boys encounter another level of wood timbers. Nevertheless, they continued toiling in the pit, removing one barrier after another in hopes to claim their mysterious reward. When the teenagers pulled away the second platform of wood timbers only to find another layer of soil staring back at them, the team decided to suspend their work at the site (Harris, 1967).

Several weeks later, the young fortune-seekers returned to the pit with their pickaxes and shovels. However, the second attempt for the boys proved similar to their initial outing. After hours of laboring beneath the June sun, removing ten more feet of dirt from the deepening hole, they were once again confronted by a table of thick timbers embedded in the clay of the tunnel wall (Harris and MacPhie, 2005). McGinnis and his companions continued down five more feet before defeat set in and the boys stopped their treasure hunt.

Although the first attempt proved fruitless, the legend of Oak Island's Money Pit still had many secrets to reveal. Perhaps too convinced of treasure to give up the pursuit, the eldest of the excavators, John Smith, purchased the lot containing the intriguing cavernous pit that same month. However, interest in the peculiar hole was not limited to the teenaged McGinnis, Vaughan and Smith. In fact, more mature and experienced minds would soon succumb to the prospect of wealth contained in those shadowy depths. According to Harris, in 1803, Simeon Lynds joined the excursion. Lynds was the grandson of a pioneering family from Ireland who settled in Nova Scotia in 1761 (1967). Simeon's father, Thomas Lynds fell in love and married Simeon's mother, Rebecca Blair in 1774 (1873). Rebecca was the fifth daughter of Captain William Blair, a Scottish immigrant who had moved his family north from New England to help suppress the French forces at Louisbourg. Perhaps it was his maternal grandfather's daring nature coursing through his veins when, in 1803, the pit's discoverers convinced Simeon Lynds to continue the hunt. Lynds was a relative of the Vaughan family and was listed as a "wheel-wright," in historical records. To assist with his new adventure, Lynds enlisted the help of Colonel Robert Archibald, Captain David Archibald and Sheriff Thomas Harris. Together, the group established the Onslow Company, a professional venture with the sole purpose of recovering the Oak Island treasure.

The renewed effort began in earnest in the summer of 1804. That year, the team returned to the pit for what they hoped would be the third and final attempt at uncovering the supposed riches. Lynds and his men started by removing the backfill from the initial excavation. Just as the first team indicated, the Onslow Company noticed marks in the clay walls nearly every ten feet where the wooden timbers had been removed. After the first 25 feet, the excavators found themselves in unexplored territory. From this point, every shovelful came with the promise of discovery. At a depth of 30 feet, one of the laborers hit a solid object. Removing the soil, the crew found that another timber level had been installed inside the tunnel (Lamb, 2006). This time, however, the men noticed the remnants of charcoal scattered around the platform.

Baffled, the crew disposed of the wooden barrier and continued their search. Digging 10 more feet, the enthusiastic men of the Onslow Company found themselves standing on yet another shelf of horizontal timbers. This time, rather than charcoal, the diggers observed a sap-like substance along the seams between the logs. Whatever was stored beneath must have been worth the trouble of encapsulating the tunnel for protection. The men resumed their efforts, encouraged by the added elements of charcoal and sealant.

Burrowing another 10 feet, the team encountered something they would have never thought possible. Atop another platform of timbers were scattered the fibers of coconut shells (Harris and MacPhie, 2005). To the men, this development seemed to underscore the importance of their efforts. Although the coconut fibers themselves held no commercial value, there were two reasons the Onslow Company crew considered the debris reassuring. First, as could be assumed, coconuts are not native to Canada. The most likely source of this tropical fiber would have been somewhere in the Caribbean. Secondly, the reason the material probably came from the Caribbean, was that, in a time of long voyages on the high seas, coconut fibers were used to secure and protect valuable cargo. The matted brown fiber could mean a hoard of precious goods was stashed deeper within the pit.

The men wasted no time in dispatching the floor to claim their bounty. To their dismay, the pit was not yet ready to reward the anxious treasure hunters. From the 60-foot depth where the coconut fiber was found, it would take the men another 30 feet of digging and the removal of two additional timber barriers before they would make a significant discovery.

There, at a depth of 90 feet beneath the surface of the tiny Canadian island, the weary team of fortune seekers uncovered their first precious stone. What the men found was not a diamond or any type of gem, but a large square-cut stone tablet. On the face of the heavy stone was an inscription of strange symbols. Each character of the mysterious text consisted of a unique combination of lines, arrows and dots. Despite its significant weight, the crew hoisted the rock from the pit for further examination (Lamb, 2006).

For decades, the encoded message on the face of the rock was thought to be indecipherable. During this time it was rumored that Smith used it as a fireback in his fireplace, while others claim it was used as a doorstep to a Halifax bookbinder's shop or possibly even displayed in the window as an enticement to potential expedition financiers.

It was not until the 1860s that an academic was able to examine the symbols and provide a credible translation. Although this fact, like many involving Oak Island, remains disputed, many believe that Dalhousie University Professor of Languages James Leitchi successfully decoded the tablet's inscription. Borrowing a page from Edgar Allen Poe's "The Gold Bug," Leitchi employed a technique termed simple substitution cipher whereby unique symbols correlate to specific letters in a given alphabet. For example three vertical lines similar to this "|||" might substitute for the letter "E." Once a rational scheme is set for the symbols present in the code, a context for each letter can be constructed and meaning is extracted from the text. Applying this approach to cryptography, Leitchi resolved that the stone from the Money Pit read (Lamb, 2006):

Since the tablet was discovered 90 feet below ground, excavators subscribing to Leitchi's translation set their sights on a depth of 130 feet. Given the verbiage used in the text, members of this school also believed the treasure to have been buried by someone of British origin with a flair for the eccentric. To those who hold dearly to legends of pirates and their tie to buried gold, Captain Kidd seemed a likely candidate to construct the elaborate pit and create the mysterious stone.

With the stone out of their path, the men of the Onslow Company resumed the excavation. Expecting to dig 10 more feet before hitting another timber structure, the team was surprised when, at a depth of 98 feet, they found their next wooden obstacle. At that point, the men were exhausted from a strenuous day. The workers decided to make one last cursory attempt before resting. Rather than go through the effort of removing the logs, one of the workers used a crowbar to probe between the timbers to ensure treasure was not immediately beneath their feet. The metal rod pierced a sealed seam between two of the timbers to feel for any potentially valuable objects (Crooker, 1993). With no evidence of impending fortune, the team retired for the day.

When the members of the Onslow Company returned to the site, they found themselves confronted by another unexpected challenge. It turns out that while the team took time to rest, much of the cavernous pit had filled with water. Now, the prospect of retrieving any sort of riches lay nearly 63 feet beneath a watery chamber. The startled crew desperately began filling buckets to drain the pit. Feverishly, they scooped away the cloudy water without success. It soon occurred to the hapless crew that every time water was removed from the well, it was somehow instantly replaced. Colonel Robert Archibald noted this peculiar situation and temporarily seized operations at the site (Lamb, 2006). The Onslow Company promptly realized that the sophistication of the pit would require more than mere brute force to burrow past levels of dirt and timber. Somehow, the tunnel had been engineered to toy with men as they sought her fortune.

Staring into a well that could hold unfathomable fortunes, the members of the Onslow Company refused to admit defeat. Instead, in autumn of 1804, the group decided to employ technology to overcome the pit's defiance. To this end, they hired Mr. Carl Mosher and his mechanical pump to clear the tunnel and allow the men to resume their work. Immediately after Mosher installed and operated the pump, the company appeared to have finally earned a streak of luck. The water level slowly began to recede down the clay wall. Perhaps the water was a minor stumbling block that would only serve to rinse the gold coins before their retrieval (Crooker, 1993). Then, at a depth of approximately 90 feet, just eight feet shy of where they had previously left off, Mosher's water pump failed along with the excavators' short-lived fortune. Without the pump functioning, water steadily returned to the pit, dissolving the crew's hopes of a hasty solution. The team decided to retreat and regroup.

The following year, the Onslow Company returned to the pit with a new idea to capture the treasure. Despite the first two attempts depleting much of company's financial resources, the men believed this new approach would more than pay for past failures. Rather than concentrate on the pit itself, in 1805 the Onslow Company determined that they could bypass all of the tunnel's snares by simply avoiding the pit altogether (Lamb, 2006).

Their revised strategy included excavating a shaft parallel to the pit. At about 110 feet, once the men were beneath the supposed water trap, they would tunnel over towards the pit to collect the treasure and return to the surface. The crew would be back on the mainland, celebrating their newfound wealth in a matter of weeks. The site of the auxiliary tunnel was situated 14 feet southeast of the original hole (Harris and MacPhie, 2005). Eagerly, the men set to work, their shovels flinging dirt from the promising new shaft. It was not long, however, before the promise faded to disillusionment. At a depth of just 12 feet, water found its way into the new tunnel. With dampened spirits and drained finances, the Onslow Company finally was forced to accept defeat.

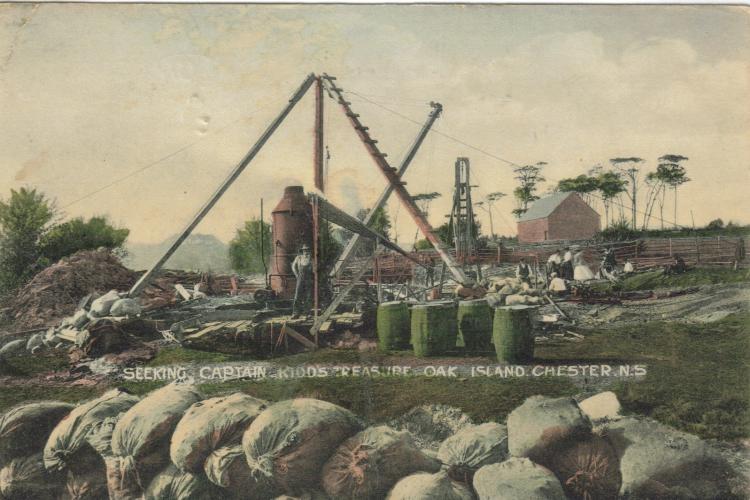

Following the Onslow Expedition, the strange site on Oak Island lay undisturbed and submerged beneath volumes of water for nearly 40 years. Then, in 1845, fervor for the entombed mystery was reawakened. That year a member of the original dig, Anthony Vaughan, helped form the Truro Company. Together with John Gammell, Adams Tupper, Robert Creelmand, Esq., Jotham McCully and James Pitblado, the treasure-seeking Vaughan anticipated success. Also joining the Truro Company efforts was the brother of the Onslow Company's Simeon Lynds, Dr. David Barnes Lynds (Harris, 1967). With this team, the Truro syndicate represented an impressive collection of qualified and respected individuals.

In spite of the ambition surrounding the newly formed Truro Company, the men did not start further exploration until 1849. With improved funding and organization, the Truro Company began the fourth attempt at solving the Oak Island mystery. In the summer of 1849, the team arrived at the site and continued where the Onslow Company left off; removing water from the pit. After two weeks of laboring against the debris and water of the pit, the crew achieved a depth of 86 feet. These gains, however, did not last. The next day, workers were perplexed to find that the surface of the water had returned to 60 feet (Crooker, 1993).

Decidedly more prepared than their predecessors, the Truro Company was determined to reveal the tunnel's contents, even if human hands did not make the initial discovery. Seeing that the water had returned, the men fashioned a wood platform that they mounted over the mouth of the pit. Through an opening in the floor of the structure, the men plunged a hand-operated auger into the waters below. They hoped this contraption would give them an idea of what was buried beyond the 98-foot deep timber floor. The results of the remote probing could not have been anticipated by even the most optimistic among them (Harris and MacPhie, 2005).

According to Crooker, the auger initially only confirmed information the men already knew (1993). At a depth of about 98 feet, the auger came in contact with a layer of spruce approximately 6 inches deep. Following the log surface, the auger sunk through one foot absent of any material. This was consistent with Vaughan's past experiences with the pit. After every wooden platform, the excavators found a pocket of air from dirt that had settled below. To Vaughan and the others, it would follow that after another nine feet; the auger would again reach a wood surface and repeat the process. Surprisingly, the hand-powered drill delivered very different results.

Beneath the layer of settled dirt, the Truro Company noticed that the auger then penetrated a series of strata consisting of 4 inches of oak, followed by 6 inches of spruce, before entering seven feet of clay. To the crew, the oak and spruce represented more than just a new configuration of wood platforms. After so many failed attempts, this could finally be a chest containing the riches they sought. When the operators withdrew their probe from the pit, they were given even more reason for excitement. Attached to the auger, the men of the Truro Company found three small links of gold chain (Lamb, 2006). Between the wooden object buried beneath the timbers and the metal retrieved by the auger, the men were certain of their victory.

Bolstered by the success of their initial drilling, the Truro Company sent the auger down for another attempt. This time the probe was cast to 114 feet beneath the surface. At this depth, the auger hit another platform of timbers. Although no additional gold was retrieved from this drilling, the device did produce further confirmation of oak and coconut fibers. With the exception of gold coins, the drilling had produced convincing proof that some sort of cache lie buried below.

Perhaps the most convincing evidence that treasure was close at hand was furnished by human behavior amongst the team. According to Lamb, Truro Company foreman James Pitblado did something very peculiar following the fourth drilling (2006). As the auger brought materials to the surface, other crewmembers witnessed Pitblado wipe dirt off an object before discreetly slipping the item into his pocket. Several accounts of the event indicate that immediately after this episode, Pitblado left the island and relinquished all ties to the Truro Company expedition.

Although Pitblado disappeared that day, he would not be absent from the narrative for long. Whatever Pitblado pocketed from the drilling debris had inspired him to petition the provincial authorities for a license to conduct his own excavation on the island. To help back his venture, Pitblado convinced lawyer and recognized businessman Charles Dickson Archibald to join him. Unfortunately for the two, the only official privilege they were granted by the government was the right to continue their search on "ungranted and unoccupied" lands. Essentially, the splinter group of fortune hunters could only seek treasure on property not already deeded to a private owner (Crooker, 1993). This restriction barred the men from exploring the enigmatic Money Pit. After a rejected attempt to purchase the lot containing the pit, Pitblado and Archibald were forced to leave finding the potential riches to the Truro Company. Archibald eventually retired to England while the duplicitous Pitblado and his unknown trophy disappeared into the fog of history.

Despite the promising developments in 1849, the men of the Truro Company left the site for the season. When they returned in the summer of 1850, the team brought with them a renewed sense of purpose and a refined strategy to extract their wealth. Similar to the Onslow Company's second effort, the members of the Truro Company devised a plan that would descend a shaft parallel to the original tunnel. At a depth of 109 feet, the new tunnel would burrow horizontally, thereby entering the Money Pit (Harris and MacPhie, 2005). A daring spelunker would then collect the coffers and return to the surface to celebrate. As could be expected, the island would not succumb so easily.

Similar to previous attempts, before the adjacent access shaft could reach the intended depth, the new tunnel filled with water. While not the result the crew had intended, this episode did offer an important discovery. As the team worked to drain the deluge, the laborers made two valuable observations. First, the water present in the shaft was salty. Second, the level of the water rose and fell with the tide. Although simple, these observations had profound implications. Previously the company thought that the Money Pit was being inundated with water as either part of a complicated trap or as a result of the natural water table. Now the team knew that somehow it was the surrounding sea that flooded their excavations.

Equipped with this new knowledge, the Truro Company investigated the area for more clues. As though a veil had been lifted, the men discovered that a southern portion of the island's shore was actually manmade (Crooker, 1993). The company decided to build a temporary rock dam in Smith's Cove to see if the key to the mystery could be found outside the actual tunnel.

With the water held behind the cofferdam, the crew uncovered remnants of a previous dam as well as five peculiar vent openings. Tracing the vents back to shore, the investigators tried to determine whether the shafts converged into one before continuing inland toward the pit. Here, their suspicions were confirmed. In order to drain the Money Pit, the team would either have to empty the Atlantic Ocean or obstruct the feeder vent that connected the five shafts to the tunnel. They chose the latter. After two attempts to find the feeder vent, the crew succeeded and wedged wood pilings into the shaft to prevent further flooding. Thinking they could now remove the water and claim any treasure, the men were puzzled to find that, despite their best efforts, the water level refused to lower. The confused Truro Company ultimately broke camp and left empty-handed from the 1850 expedition. Deflated and destitute, the company disbanded the following year (Harris, 1967).

In spring of 1861, the next group of hopeful treasure hunters was formed. They were named the Oak Island Association. Under the agreement to give the property owner, Anthony Graves, one third of all findings, the group began work at the Money Pit (Crooker, 1993). At first, the men of the new expedition found the task to be an easier challenge than expected. They soon had cleared the main tunnel down to 88 feet, and had excavated two parallel tunnels to 118 and 120 feet all with no sign of flooding. The 118-foot shaft was dug 18 feet west of the Money Pit. The plan was, at that depth, the excavators would begin tunneling east to access the entombed loot. However, just one foot from penetrating the Money Pit, water flooded the access tunnel (Harris and MacPhie, 2005).

With so little earth between them and the promise of treasure, the Oak Island Association utilized a pumping gin to clear their watery path. After three desperate days of trying to drain the shaft with no results, the company turned their efforts towards the other access tunnel 25 feet from the Money Pit. Already at a depth of 120 feet with no sign of water, the crew determined to burrow horizontally from this new direction. Here again, with the main chamber just feet away, the second access tunnel was inundated with water (Crooker, 1993). For two days, the 63 men of the company struggled to dredge the shaft to no avail.

Down but not out, the team decided to send surveyors into one of the access tunnels in an effort to assess the cause of the flooding. As two men labored in the shaft, those aboveground heard a loud crash. The thankful surveyors made it out alive as water began rushing into the tunnel. With everyone safely at the surface, the crew heard another startling sound. This time it was the Money Pit causing the commotion. According to Harris, beneath the weight of the oncoming water, the timbering installed to support the sides of the Money Pit collapsed everywhere below 30 feet from the opening (1967). Along with the partial wall collapse, further inspection revealed that the bottom of the tunnel had also given way. The depth of the hole now stood at approximately 112 feet.

Although startling, no one was injured during the event. On the contrary, this episode may have helped heal the concerns of the team. As it turned out, when the floor of the Money Pit failed during the flood, pieces of debris from below washed upward through the murky water. When the men inspected the scene, they discovered several curious items including the bottom of a yellow dish, a piece of Juniper worked at either end of the wood, an oak timber, and a spruce slab scarred by the hole left by a drilling auger (Crooker, 1993).

As the 1861 digging season moved forward, the Oak Island Association remained steadfast in their efforts. Perhaps encouraged by the debris, the men installed a cast iron pump and steam engine to dispatch the water in the pit. Although pumping operations on Oak Island had become a standard practice for teams of treasure hunters, this particular attempt would have a lasting impression on the hopeful crew. In fall of 1861, as the company struggled to drain the tunnel, a boiler exploded fatally scalding one operator and injuring several others. This fatality represented the first death inflicted by the Money Pit (Harris and MacPhie, 2005). To the regret of many, it would not be the last.

Despite the tragedy, the men of the Oak Island Association returned to the site over the next four years. Following the incident, much of the group's efforts involved locating and obstructing the feeder tunnels from Smith Cove thought to be responsible for the flooding. Although these attempts also failed to produce results, there was no further loss of life among the ranks of the Oak Island Association. In 1866, the company relinquished its rights to search for treasure at the site, ending a costly and tragic campaign in the Oak Island narrative.

Ineffective attempts by misbegotten treasure hunters persisted for much of the 19th century, with little more than mounting debt and sinking hopes to show for the investment. Then, in 1890, excitement for the enigmatic tunnel was reignited when a one and a half ounce copper coin was discovered on the island (Harris and MacPhie, 1999). Although the copper piece was found outside of the Money Pit, to many observers, it served as yet another testament to the wealth buried below.

Energized by the new potential, in 1893 Frederick Blair and S.C. Fraser incorporated the Oak Island Treasure Company in the state of Maine. Under a $30,000 lease agreement, the organization secured exclusive rights to all treasure discovered on the property for a period of three years (Crooker, 1993).

Despite the enthusiasm of the Oak Island Treasure Company, the organization's efforts proved despairing even from the start. Initially, when the fledgling association met in Truro to appoint officer positions and generate revenue, the group was unable to raise enough capital to cover the purchase of a pump (Harris, 1967). Without this essential piece of equipment, the company would scarcely be able to move forward with the expedition. Regardless, the group decided to take aggressive action and began a deliberate excavation in 1895. Unfortunately for the crew, they had unknowingly been laboring within one of the auxiliary access tunnels 10 feet northwest of the Money Pit itself. To make matters worse, the team had dug down to 55 feet before the chamber was inundated with water and work was interrupted (Harris and MacPhie, 2005).

Several months later, the Oak Island Treasure Company was confronted by additional difficulties. In September of 1895, the Attorney General of Nova Scotia informed Frederick Blair that, in spite of the lease agreement, any treasure acquired as a result of their expedition belonged to the Queen, represented by the provincial government. To encourage continued digging, officials of Nova Scotia agreed to claim only a portion of the riches recovered from the island (Harris, 1967).

The following year, with the assistance of a new pump, the company returned to Oak Island. However, this attempt proved uneventful when, at a depth of 70 feet, the pump failed to keep up with the water flow and work was suspended (Crooker, 1993). However, the trend toward the mundane was abandoned in 1897 when tragedy again visited the island. On March 26th of that year, a man named Maynard Kaiser was working in one of the many shafts drilled into the terrain. As he was being hoisted to the surface, the ascension rope carrying Kaiser slipped from the pulley, casting him back into the shaft to his death (Fanthorpe, 1995). Following the accident, several crewmembers felt convinced that the treasure was either cursed or protected by a malevolent spirit and refused to descend into the Money Pit.

Whether or not they were confronting a paranormal guardian, in June of 1897 the Oak Island Treasure Company again tried their luck at acquiring the presumed fortune. After only moderate success in draining the Money Pit, the team followed the lead of their predecessors and relied on drilling to uncover whatever was buried below. Unbeknownst to the company, their findings that day would taunt innumerable imaginations for years to come.

According to Lamb, the team first drilled down 126 feet, encountering a five-inch layer of oak before hitting an impenetrable iron surface (2006). The men moved their drill one foot from the initial hole and executed a second attempt. Here, the auger passed through layers of soft stone, oak and a deposit that seemed to consist of loose pieces of metal. Encouraged by the results, the team sent the drill back down the same borehole. At a depth of approximately 153 feet, the drill again came in contact with what the team perceived to be loose metal. Beneath the supposed metal the auger encountered the same iron barrier and could not descend further.

When the drill returned to the surface and the team examined the boring extracted from the pit, excitement soon faded. Despite the layer thought to be loose metal, the men only found pieces of coconut fiber, oak splinters and loose debris. At first, this appeared to be no different than previous attempts. However, upon closer examination, the debris pulled from the tunnel that day would ultimately invite theories once considered outlandish.

While the men continued drilling at the site, the extracted debris was transported to a courthouse in Amherst, Nova Scotia. There Dr. A.E. Porter subjected the materials to closer examination. After scrutinizing the Oak Island debris, Dr. Porter made an alarming discovering. Amongst the dirt and rubble, he found an unmistakable piece of parchment. Further distinguishing the fragment was what appeared to be the letters "VI" written on one side of the material (Crooker, 1993). Eventually the tiny script was inspected by Harvard University specialists who verified its authenticity (Harris, 1967).

Another discovery made during that excavation only came to light many years following the summer of 1897. As indicated by Lamb, during that fateful excavation, drill operator William Chappell found traces of gold sediment on the auger after drilling into the Money Pit (2006). Similar to James Pitblado, formerly of the Truro Company, Chappell hid his valuable discovery from fellow crewmembers. It was not until 1931 that Chappell's findings would come to light.

The next year, a less lucrative yet equally significant discovery was made. Given the amount of flooding in the Money Pits and surrounding auxiliary holes, excavators believed the tunnels were somehow interconnected, forming a sophisticated labyrinth. To test their theory, members of the Oak Island Treasure Company decided to pour colored dye into the Money Pit. The crew reasoned that by tracing the path of the pigment, they could determine the locations of the various flood channels and ultimately obstruct them once and for all. When the team set their plan into motion, they were astonished to find the dye streaming out from the shoreline at distant points around the island's perimeter. Perhaps most astonishing was that the coloring did not appear in Smith Bay where structures thought to be flood tunnels were located in 1862 (Harris, 1967). Further perplexing the crew was that, after multiple attempts to dynamite the feeder channels, they seemed unable to clog the pathways and prevent further flooding.

For decades, the company continued its efforts on Oak Island, transitioning from the Oak Island Treasure Company to the Old Gold Salvage and Wrecking Company in 1909. Despite the increase in capital and experience the excavators received from the acquisition, success eluded the teams throughout the early 1900s.

To claim that all of the treasure hunters were somehow misguided would undermine the credibility of even an acclaimed United States president. In 1909, at the age of 27, Franklin Delano Roosevelt joined the ranks of the Old Gold Salvage and Wrecking Company. The affluent, Harvard-educated Roosevelt spent that summer off the shores of Nova Scotia, as hopeful to find the treasure as any who had preceded him. According to written correspondence, Roosevelt nurtured an interest in the Oak Island mystery well into his presidency. In a letter to a friend, the president intimated his intentions to return to the island on Mahone Bay, but was prevented from doing so by the outbreak of war in Europe (University Archives, 1939).

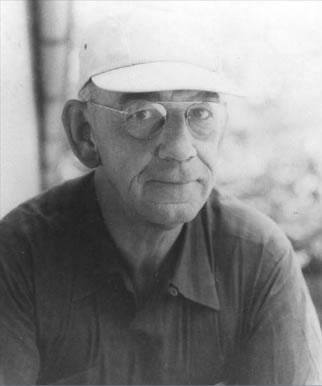

Originally part of the Oak Island Treasure Company, William Chappell was noted to have found traces of gold on an auger during an 1897 excavation. Although he initially kept his discovery a secret, many years later Chappell confided the details of what he had found to Frederick Blair. In 1931, founder of the Oak Island Treasure Company, Frederick Blair maintained the lease on the Money Pit property. In an effort to garner Blair's support as well as his permission to drill at the site, Chappell described his encounter with the gold dust. Convinced of their impending fortune, Blair signed on with the new expedition under Chappells Limited of Sydney, Nova Scotia (Crooker, 1993).

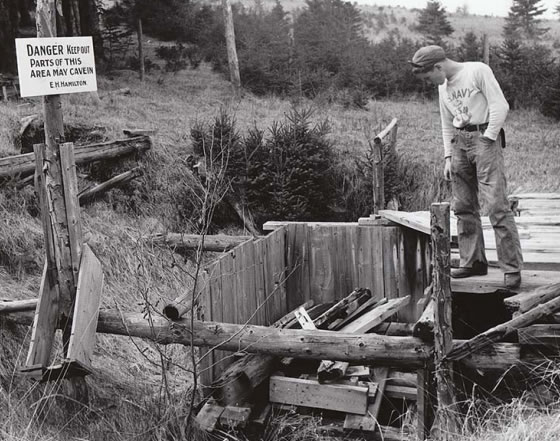

The two men along with Chappell's brother Renerick, son Melbourne and nephew Claude, began work in 1931. Like many before them, the group found themselves with far more enthusiasm than solutions. The first problem they faced was discerning exactly which hole in the ground was actually the Money Pit. By that year, the site had undergone nearly a century and a half of excavation efforts, marring the island's surface with shaft openings. Mistakenly, the team ended up drilling approximately six feet south of the Money Pit (Harris, 1967).

The duration of the Chappell expedition was short-lived; only active for one digging season. However, the team was able to make several astonishing discoveries during their brief stay. All between 115 and 130 feet deep in their new shaft, the men recovered an anchor flute sunk into the side of the tunnel, an implement resembling a 250 year-old Acadian axe, a miner's pick and the remnants of an oil lamp with seal oil (Crooker, 1993). Adding to the intrigue of the site, Mel Chappell also located a triangular formation of stones situated along the south shore of the island. Individually, each of these findings would be significant, but together, perhaps they provided more insight into the mystery of the island. Unfortunately for Chappells Limited, with $40,000 invested in the project, the team lost its lease to excavate the site and was forced to suspend operations in 1932.

A man named Gilbert Hedden initiated the next significant effort at Oak Island. While several of his predecessors were qualified and even intellectual men, Hedden had perhaps the best combination of resources to be successful at extracting the fabled treasure. Prior to his interest in the Money Pit, Hedden was Vice-President and General Manager of the Hedden Iron Construction Company of Hillside, New Jersey. In this capacity, Hedden grew increasingly familiar with the application of structural steel in engineering. His career also provided Hedden with the financial means to pursue the promise of the Money Pit when his company was purchased by the Bethlehem Steel Company in 1931.

According to author Mark Finnan, Hedden became interested in the Money Pit in 1928 after reading an article on the topic in the New York Times (2002). The steel magnate was convinced that the tunnel contained the fabled treasure of pirate captain William Kidd. By 1935, his interest had heated to a passion. That year the affluent Hedden purchased the eastern portion of Oak Island and had arrived at an agreement with Frederick Blair securing access to the Money Pit (Crooker, 1993). To undertake the pumping and excavation, Hedden hired Sprague and Henwood, Inc. of Pennsylvania. Having obtained legal access to the property and the means to excavate the buried treasure, Hedden began his expedition in 1936.

The results of his team's first digging season were unimpressive. Sprague and Henwood, Inc. used electric turbine pumps to remove seeping water as they re-excavated and reinforced Chappell's shaft just south of the Money Pit. Similar to Chappell, the shaft only produced disappointment as the 1936 attempt ended with Hedden leaving empty-handed (Harris and MacPhie, 2005).

In 1937, Hedden and his contractors returned to Oak Island. This time the company would encounter intriguing findings. Burrowing down one of the many auxiliary tunnels pock marking the island, the team stumbled upon a number of fascinating items including a miner's oil lamp with whale oil and unexploded dynamite at 65 feet. At a depth of 93 feet, they unearthed clay putty not previously found on the island. Slightly further down in the tunnel the men made an even more encouraging discovery. At a depth of 114 feet, Hedden's team came across an intersecting tunnel measuring 3 feet and 10 inches wide by 6 feet and 4 inches tall. Remarkably this chamber was lined with hemlock timbers and may have served as one of the original flood tunnels (Harris and MacPhie, 2005).

Although promising, the elements discovered in 1937 did nothing to offset the increasing expense of the excavation. At the close of that year's dig, Hedden's operation had reached a cost of $50,000, an exorbitant amount even for the most endowed financier. However, following the publication of Harold Wilkins' Captain Kidd and His Skeleton Island, Hedden felt his investment in the search was vindicated. Along with a treasure map resembling Oak Island, the work of fiction provoked readers with irrefutable similarities to the Money Pit narrative. Captivated, Hedden traveled to London to learn the source of the author's information. To Hedden's dismay, Wilkins was surprised to hear of any parallels between his tale and the site in Nova Scotia (Crooker, 1993).

While Hedden maintained his interest in what he believed was pirate treasure, in 1938 he halted his drilling campaign to concentrate on business matters (Harris, 1967). Despite abandoning excavation efforts, Hedden felt that the clues he uncovered during his investigation deserved the attention of British royal and fellow Freemason, King George VI. According to author Mark Finnan, in 1939 Chappell drafted correspondence to his majesty, highlighting the unique importance of the Money Pit on Oak Island (2002).

Since its discovery in 1795, the Money Pit has elicited a number of legends and tales to help explain the mystery of Oak Island. Among the stories created by those grappling with the enigma is that the treasure will evade discovery until seven people die trying to capture it. If this folklore holds any truth, the Restall expedition of the 1960s did the most to fulfill the tragic prophecy.

Prior to arriving on Oak Island, Robert Restall had become well acquainted with adventure. In fact, not long after meeting and marrying his young wife, Mildred, Restall enlisted his bride in a spectacular traveling show. The act was called the "Globe of Death" and involved the couple whipping around a large steel sphere on motorcycles at speeds up to 65 miles per hour. The daredevils performed throughout Europe in the 1930s before moving their act to Canada. By 1955, the couple had settled in Hamilton, Ontario and was raising two sons and a daughter (Restall, 1965).

As Mildred Restall described in 1965, once Robert had heard about the Money Pit mystery, it became his pursuit. He set out collecting articles and information on the site, determined to learn everything about the island including the reasons others had failed. After years of building enthusiasm, Restall negotiated a deal with owner Mel Chappell in 1959. In exchange for 50 percent of any recovered treasure, Restall was given full rights to operate at the pit. Within the month, Restall relocated him and his eldest son to the modest island (Restall, 1965).

The former stunt drive turned plumber began his excavation supported by $8,000 of capital and equipment. Some of this had been borrowed from outside investors while the remainder of it represented the family's own savings. Immediately, Restall and his son set to work. By July of 1960, the two managed to remove water from the main shaft to a level not seen in decades (Lamb, 2006). That year the rest of Restall's family moved to Oak Island to help in the excavation.

Over the next five years, the Restalls dedicated their lives to Oak Island and the pursuit of the fabled riches. The family lived in two primitive cabins void of running water. Their fresh water was gathered from snowmelt and rain collected in a depression left by a dynamite blast many years before. At times they would visit the mainland for supplies, but would always return to Oak Island driven by Robert Restall's constitution and certainty that he would capture the pirate's bounty (Restall, 1965).

Sadly for Mildred, this unique chapter in her family's history ended abruptly on Tuesday, August 17th, 1965. As she recalled, her husband intended to visit Halifax that afternoon. Restall and his son had been working on digging a new shaft on one of the beaches. Sometime after 2:00 PM, as Restall peered over the edge of the tunnel to inspect his work, he succumbed to noxious gas emanating from the pit (Restall, 1965). Restall then lost consciousness and fell into the watery shaft. When his son, Bobbie, witnessed this episode, he dashed in after his father only to be claimed by the toxic fumes as well. Unaware of what was unfolding, two nearby workers, Karl Graeser and Cyril Hiltz, also rushed in to help. Both suffered the same fate as the Restall men (Lamb, 2006). At the close of this fateful day, Oak Island had claimed a total of six people since the mystery began.

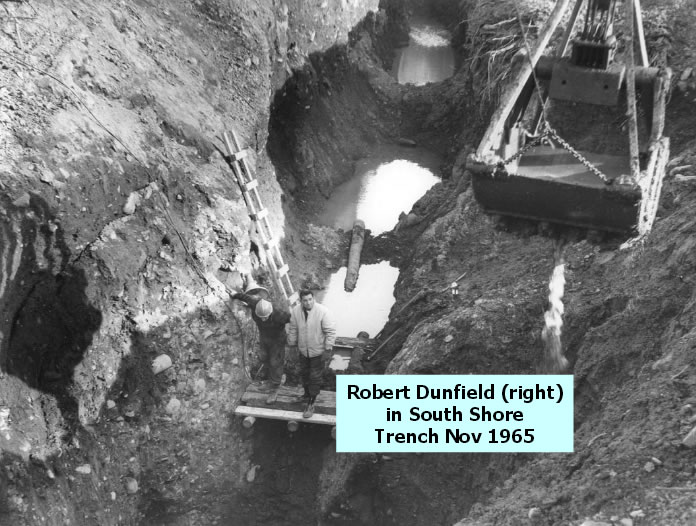

Just over one month before the tragedy that claimed the lives of four men, Robert Restall signed an agreement with investor and Geologist Robert Dunfield. After Restall passed away, Dunfield assumed control of operations at the island. Rather than make small incisions at strategic locations, Dunfield's approach involved a much more dramatic approach. In fact, Dunfield's first order of business as project manager included using two bulldozers to clear 12 feet from the surface of the Money Pit and spread the removed clay over Smith's Cove as a way to clog any feeder tunnels that might be flooding the main chamber (Crooker, 1993).

In order to transport even larger excavation equipment to the site, Dunfield ordered a causeway be built connecting the west end of Oak Island to Crandall's Point on the mainland. Completed on October 16, 1965, the causeway stretched 600 feet and consisted of 1500 cubic yards of compacted fill (Crooker, 1993). With the land bridge in place, Dunfield could move operations beyond lightweight machinery. Within weeks, the geologist had brought a 70-ton digging crane to Oak Island and was preparing to excavate at a scale never before seen at the site.

The month following the crane's arrival, Dunfield and his crew dug in. Assisted by the modern equipment, the team removed a 140-foot deep by 100-foot wide crater from the Money Pit. The effort proved bitter sweet as the team uncovered small shards of porcelain dishware but consistently struggled against the tunnel's collapse as a result of heavy rains (Harris, 1967). When Dunfield suspended work for the season in November of 1965, the expedition had already accrued an expense of $60,000.

Immediately after New Year's Day of 1966, Dunfield returned to Oak Island. Despite having spent countless hours and dollars excavating the main tunnel, he demanded that the Money Pit be refilled to create a base for a drilling campaign. Once his men had finished filling the gaping cavity, Dunfield began taking core samples at greater depths. He drilled four separate 6-inch holes to a depth of 190 feet into the Money Pit. From this investigation, he concluded that at approximately 140 feet a wooden platform obstructed the tunnel. Below the timbers was a 40-foot chamber void of any material. This empty space was followed by bedrock. Intrigued by these findings, Dunfield sent the core samples to the University of Southern California to undergo chemical analysis. Although he kept the results confidential, they encouraged Dunfield to announce his intentions for further large-scale drilling operations in the main tunnel (Harris and MacPhie, 1999).

The next several months were perhaps more frustrating than fruitful for Dunfield and his team. After excavating several promising locations across the island, he was unable to find anything more than the previous shards of porcelain and core samples. Further complicating matters, treasure-seeker and Oak Island property owner, Fred Nolan, bought lots immediately adjacent to Crandall's Point. Frustrated that Dunfield would not allow him use of the causeway to the island, Nolan barred its entrance from the mainland, essentially prohibiting both parties from the costly land bridge (Crooker, 1993). Whether a result of the $130,000 price tag or the feud with Nolan, in April of 1966, Dunfield left the project and returned to California.

Prior to the formation of the Triton Alliance, key partners Daniel Blankenship and David Tobias had been investigating the plausibility of the Oak Island narrative. In 1967, the men had made their assessment and decided to actively pursue the alleged treasure by purchasing the majority of the island. Given the recent tension between Dunfield and Nolan, the two investors knew that their undertaking would need to be political as well as technical. Taking conciliatory measures, Blankenship and Tobias initially enlisted both Dunfield and Nolan to assist in their expedition (Harris, 1967). This move ensured their access to the valuable causeway and Dunfield's knowledge of the island.

Under the tentative truce between the treasure hunters, Blankenship and Tobias began an ambitious drilling campaign. Throughout 1967, the men bored over 60 holes into the surface near the Money Pit. From their drillings, the two ascertain that bedrock began at a depth of 160 to 170 feet. They also found that, at certain locations, there was a wooden level 40 feet beneath the bedrock. As they continued their coring, Blankenship and Tobias retrieved a piece of brass from a site they termed Drill Hole 21. From similar test holes, they found pieces of porcelain, wood, clay and charcoal (Harris and MacPhie, 2005).

In 1969, the expedition began in earnest when Blankenship and Tobias formed the Triton Alliance Limited. The new company wasted no time in their efforts to retrieve the mysterious fortune. Selecting strategic locations outside of the Money Pit, the Triton Alliance employed a calculated approach to their expedition. That year, in a test pit 180 feet northeast of the main tunnel, the Triton crew noted finding a small amount of metal at a depth of 160 feet. Additional metal samples were found in 1970 at various depths northeast of the Money Pit. Also in 1970, during an excavation attempt in Smith Cove, workers uncovered a U-shaped formation of logs marked with Roman numerals. The construction was thought to be the remnants of an ancient dam or harbor (Crooker, 1993). Adding to the excitement of the Smith Cove investigation, the Triton Alliance team discovered a pair of wrought-iron scissors, a wooden sled, a portion of an iron ruler and other iron artifacts including nails and spikes. When sent to the Steel Company of Canada for testing, these materials were determined to predate 1790 (Harris and MacPhie, 2005). The Triton Alliance now had its own evidence of human activity prior to the first Money Pit excavation.

The developments in 1971 only furthered the team's convictions in chasing the alleged riches. In January of that year, one of the most promising boreholes termed 10X was widened to fit a 27-inch diameter casing and deepened to 165 feet. During the process, the crew recovered fragments of broken concrete as well as pieces of metal chain and wire from the flooded tunnel (Crooker, 1993). Several months later, after the men had satisfactorily prepared the site, the team lowered a video camera into the watery shaft. The lens relayed grainy yet dramatic images back to observers at the surface. According to authors Graham Harris and Les MacPhie, Borehole 10X terminated in a cavity carved out of bedrock. Within the stone chamber were what appeared to be a severed hand, a corpse and several treasure chests (2005). Prompted by the video images, the Triton Alliance initiated approximately 10 diving excursions into the subterranean cavern. No treasure was extracted as a result of the divers' investigations.

Dismayed by the results of the Borehole 10X dives, the group spent the following years excavating locations across Oak Island. Then, perhaps spurred by the frustration of their circumstances, legal conflict erupted between the various interests. The first unraveling came in 1983 when the Triton Alliance brought a suit against Fred Nolan contesting his ownership of seven lots on the island and claiming their right to access the causeway extending from Crandall's Point. In 1987, after losing an appeal, the Triton Alliance was forced to pay Nolan $500 dollars while Nolan was ordered to remove an Oak Island Museum he built to obstruct entrance to the land bridge (Crooker, 1993). The strain of these legal battles combined with the stock market volatility of 1987 caused much of the activity surrounding the Money Pit to halt.

Legal issues again undermined Oak Island's stakeholders in 1989. Since 1954, the Treasure Trove Act served as the standard for regulating treasure-hunting activities. Under the provisions of the initial Treasure Trove Act, hopeful individuals were granted a Treasure Trove License. The terms of the license guaranteed 10 percent of any recovered wealth went to the provincial government. Then, in 1989, the legislation revised the original act, tightening regulations and limiting license issuance (Lewis, 2013).

With large-scale excavations stalled due to imposing financial constraints, many of those possessing interests in Oak Island turned to tourism as both a source of revenue and public promotion. Unfortunately, this type of commercial activity also required a license. Despite the additional limitations governing treasure hunting, the main players on Oak Island, including the Triton Alliance, all managed to secure Treasure Trove Licenses.

As early as the 1980s, Blankenship and Tobias were operating a tourism arm of their expedition. This entity was termed the Oak Island Exploration Company. Supported by the prominent Oak Island land holdings of the Triton Alliance, the organization enjoyed nearly exclusive access for tourism. However, members of the public interested in the island's history also began organizing their own groups. Among them was the Oak Island Tourism Society. In the late 1990s, when Tobias moved to sell his shares of the property, the Oak Island Tourism Society fervently petitioned the Canadian government to purchase the land and open it to the public. Despite the organization's protest, in 2006 the majority of the island was sold to brothers Marty Lagina (a succesful energy businessman) & Rick Lagina from Kingsford, Michigan, who along with Blankenship, formed Oak Island Tourism Inc. (Proctor, 2003).

Unfortunately for Oak Island enthusiasts, several developments around the turn of the 21st century created further complications. First, in 2009, the Oak Island Tourism Society voted to dissolve the organization, citing their inability to open an interpretive center dedicated to the Money Pit narrative. Then, in 2010, the Canadian government revisited the Treasure Trove Act. This time, rather than tightening restrictions in the legislation, officials replaced the bill with the Oak Island Treasure Act. The new law aimed to discourage exploiting Nova Scotia's cultural resources for commercial gain. As a result, "[a]nyone who wants to search for and recover in Oak Island Nova Scotia precious stones or metals in a state other than their natural state, and to keep them," would face a cumbersome licensing process with the Department of Natural Resources and would be heavily taxed on any findings (Department of Natural Resources, 2013). Since its enactment, the measure has discouraged many potential treasure seekers and has inhibited activity on the once spirited Oak Island.

In early 2014, The History Channel debuted a reality television series that documents the efforts and financial outlays of the current island owners Marty Lagina & Rick Lagina in their attempt to use modern technology to discover unknown treasure or historical artifacts, believed to perhaps be buried at Oak Island. The show details the island history, famous treasure-hunting events and discoveries, and works to solve the mystery which has been in place for hundreds of years. As seen on the show, Marty & Rick have engaged the assistance of father and son team Dan and David Blankenship, who have likewise been searching for the treasure since the 1960s, and who now live on the island.

One might like to dismiss these forlorn teams of excavators as just ignorant but optimistic wayfarers bent on imaginary riches. However, this perspective would cast such respected actors as Errol Flynn and John Wayne in the role of delusional fortune hunters. Both prominent men sought the buried mystery in the 1940s (Ricketts, 2012). Unfortunately for Flynn, a company owned by Wayne held the rights to seek treasure on the island, barring Flynn from pursuing the prize.

As with any spectacular mystery, skeptical observers have tried to degrade the Money Pit down to natural processes. Under this theory, critics maintain that Oak Island is fewer than 500 yards from the mainland of Nova Scotia. Due to its proximity, it is assumed that the two landmasses share in certain geologic characteristics. Individuals who subscribe to this school of thought point to the multitude of sinkholes littering Nova Scotia's subsurface. To these onlookers, the Money Pit is little more than a profound sinkhole worn through a susceptible limestone substrate. According to critics of the Treasure Island hypothesis, all of the artifacts recovered from the pit can be credited to debris washing into a naturally occurring subterranean cavity. This approach to the Canadian site reduces the site to a matter of geo-fluvial activity, with snowmelt and rainwater contributing the mysterious artifacts and features.

The most common theory as to what's at the bottom of the Money Pit on Oak Island is that Captain Kidd buried his vast fortune there just prior to his capture in Boston in 1699. However, others believe that Kidd might have conspired with Henry Every to use Oak Island as a type of community bank between the two. Some even believe that notorious pirate Blackbeard (Edward Teach) buried his treasure there due to him boasting that his treasure was hidden "where none but Satan and myself can find it.".

Given the international volatility present since the discovery of the New World, it should come as no surprise that the otherwise inexplicable Oak Island would come to symbolize a hidden cache of royal treasures. Two of the most favorable explanations in this category originate with either the British or French military forces.

The explanation largely hinges on British aggression against French holdings at Fort Louisbourg. Here, it is thought that at some point during the French and Indian War and subsequent Seven Years War, the Franco treasure held at the fortification was transferred to the sophisticated vault on Oak Island. There are two opposing viewpoints to this line of reasoning. Some believe that, at some point during the six-week siege of 1758, the French slipped transportation of their riches past the invading British vessels, depositing the Fort Louisbourg coffers in the aptly named Money Pit. Others deem that the successful 1758 British attack on Fort Louisbourg, ultimately led to the construction of the Money Pit for safekeeping. Under this hypothesis, British forces were ordered to systematically dismember the fallen French stronghold, pillaging its riches before depositing them beneath the island off the coast of Nova Scotia (O'Connor, 2004).

In June of 1897, the Truro Company managed to recover a mysterious shroud of parchment from the depths of the main tunnel. Written on the face of the fragment was what appeared to be the letters "VI." Although the text adds an interesting dimension to the intriguing Money Pit saga, it does not bring the hoards of explorers any closer to wealth or prestige. So why then, do so many observers feel that two letters on parchment are more significant than even gold coins? According to one theory, the answer can be found in a 16th century English playhouse. William Shakespeare was born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon in the English countryside. Although his early schooling remains debated, records indicate that Shakespeare never attended college. Instead, as a young man, he joined an acting troop and pursued theater as a profession. Through his remarkable ability as a playwright and unique talent to captivate his audiences, Shakespeare eventually earned a reputation as a literary genius. His canon of work includes 37 plays attributed to the distinguished author (Ackroyd, 2005).

However, some critics believe that the unparalleled literature of William Shakespeare is part of a real-life narrative far more cunning. To one group of observers, Shakespeare's brilliance was not in his writing, but in his ability to deceive. Citing his lack of education, travel or general experience in the world, critics believe that Shakespeare never authored any of the cherished plays. Instead, they offer that he merely claimed the works as his own to conceal the identity of the true author, Sir Francis Bacon. The theory follows that Bacon, a recognized scientist, scholar, philosopher, statesman and contemporary of Shakespeare, was responsible for penning the literature. To avoid being labeled a lowly playwright, the aristocratic Bacon secretly transferred credit to Shakespeare. According to some, Bacon embedded clues in many of the plays suggesting this arrangement (McKaig, 1985).

When the parchment containing India ink lettering was retrieve from the Money Pit, a group of onlookers were convinced of its connection to the Shakespearean conspiracy. To them, the parchment represented a fragment of the documents contained in the pit that would finally prove Bacon's authorship. Bolstering this opinion is Sir Francis Bacon's book "Sylva Sylvarum" in which he details his design of a perpetual spring. The self-flooding tunnel described in the text has many theorists convinced that in the depths of the Oak Island Money Pit lies proof of Sir Francis Bacon's true literary achievements (McKaig, 1985).

Not everyone is convinced of Professor Leitchi's decryption of the inscribed stone. Another group holds that the symbols written on the tablet date to a much earlier time. Some believe that the actual meaning of the symbols found on the rock face is as follows (Finnan, 2002):

A Harvard Zoology professor and the founder of the Epigraphic Society of America named Dr. Barry Fell was responsible for this translation. Born in 1917, Fell eventually studied ancient and foreign languages alongside his formal training as a zoologist. Through his work, Fell determined that seemingly disparate cultures, previously thought to have no contact with one another, actually shared a number of similarities between their languages and symbols. Ultimately Dr. Fell formulated a controversial hypothesis claiming that the ancient civilizations of Africa, Asia and Europe had regular contact with the Americas long before Columbus made his famed discovery.

To Fell and his followers, the Money Pit stone tablet had been created by the Coptic Christians, a numinous group of Christians rooted in Egypt. The zealous Egyptian worshippers have been credited by some as the descendants of pharaohs and the builders of the great pyramids. According to Fell, the mystical stone found on Oak Island was left by an early Coptic settlement as a warning to prevent divine wrath by adhering to strict religious practices (Finnan, 2002).

Whether the work of a pirate's hand or proof that North African Christians were active in the pre-Columbian New World remains debated. Undermining either argument is the unfortunate fact that both translations were based on depictions of the symbols on the stone rather than the stone itself. Neither Leitchi nor Fell ever actually saw the unearthed tablet with their own eyes. Instead, they relied on interpretations of the cipher relayed to them by others. Further complicating matters is that the object disappeared around 1930 and, as of this writing, remains lost.

Interestingly, many observers of the Oak Island mystery believe the inscribed stone together with a grouping of other stones on the island indicate the people actually responsible for engineering the Money Pit. While the carved tablet naturally invites interest, some feel that the cipher is merely one of a collection of uniquely compelling rocks. This explanation for the Money Pit is as sophisticated as the tunnel itself and has its beginnings in 12th century Europe.

Along with many details of the Money Pit story, what follows is anchored in as much folklore as fact. As the story goes, around 1114 A.D. a small collection of devout Christians formed a group determined to safeguard pilgrims' passage to the holy land. With their devotion to protect the sacred Temple of Solomon, the group was termed the Knights Templar. The church-affiliated Catholic Encyclopedia provides, "[i]n 1118, during the reign of Baldwin II, Hugues de Payens, a knight of Champagne, and eight companions bound themselves by a perpetual vow, taken in the presence of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, to defend the Christian kingdom" (New Advent, 1997).

The original nine men of the Knights Templar who swore to protect their faith eventually influenced a legend that would persist throughout the centuries. Through their efforts to secure Jerusalem for the Christian faithful, the Knights Templar garnered a reputation as a pious and capable military force. More importantly, some believe that, during their time in Jerusalem, the small band of monastic warriors uncovered the legendary Holy Grail. While this cannot be verified, the Knights Templar did acquire an elevated status following their victorious crusades. At their height, the Knights Templar represented nothing short of an elite sect, with the wealthy houses of Europe clamoring to enlist their sons and donate their riches. In spite of this prestige, the men of the Knights Templar eventually found themselves political targets.

Following nearly two centuries of patronage to the church, on Friday the 13th, 1307, King Phillipe IV of France and Pope Clement V resolved to abolish the Order of the Knights Templar in France and arrested hundreds of its members. The action was taken as a measure to seize the vast wealth the Knights Templar were known to have acquired. Many were tortured, executed for heresy or forced to formally relinquish their loyalty to the Order (Sora, 1999). Despite the threat of death or punishment, the affiliation thrived in the shadow of royal authority.

Some observers hold that on that fateful Friday in 1307, while religious warriors were being incarcerated and ultimately burned at the cross, the mysterious wealth held by the Knights of France was simultaneously being loaded aboard a sea-faring ship. The destination of the vessel has yet to be known. One belief is that the Knights traveled to Scotland where efforts to relinquish the Order were not pursued. To evade further persecution and, perhaps, protect the Holy Grail, the Knights formed a secret society. Similar to their previous affiliation, the new faction was imbued with religious rites and symbolism. Although active for centuries, this group did not officially make their presence known to the public until the early 18th century. According to their official history, "[t]he first Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons was established in 1717 in London" (Freemasons.org).

If it is to be believed that the Freemasons are the reincarnation of the fabled Knights Templar, than one important question persist. What happened to the Templar's treasure? According to a handful of scholars, explorers and investors, the ultimate destination for the Holy Grail and other priceless objects belonging to the Knights Templar was the famed Money Pit on Nova Scotia's Oak Island. Supporting this theory is the discovery of several peculiar stones found across the island. According to researcher Mark Finnan, throughout the years, various expeditions admitted finding an array of stones containing odd symbols. Among the unnatural shapes discovered were numerous crosses, a circle with one central dot, deliberate triangular rock formations and the letter "H" thought to be an alteration representing the Hebrew term "Jehovah." Each of these symbols is deeply rooted in Masonic traditions (Finnan, 2002). Combining the meaning of the stones with the engineered sophistication of the tunnel, many rational investigators are convinced that the Money Pit is not simply the treasure chest of a pirate. Instead, they believe it may be the site of the Holy Grail or Ark of the Covenant.

It appears far too simple to dismiss the efforts of respected lawyers, businessmen, doctors, actors and even an esteemed president. Then, it stands to reason that, if at least a handful of the countless men who visited the pit were rational and intelligent people, perhaps there is more to the story. Digging deeper into the history surrounding the site can help uncover what may lie deeper in the Money Pit. Although certainly relevant, it seems pirate treasure is not the sole explanation for the attraction of Oak Island.

Today, the Canadian site is marked by two centuries of attempts to drill for treasure. The unknown contents of the pit continue to draw speculation and seduce the imaginations of fortune seekers. Whether it holds Captain Kidd's treasure, Sir Francis Bacon's plays or even the Holy Grail remains uncertain. The one detail that is known and widely agreed upon is that the Oak Island Money Pit remains one of the greatest mysteries on the planet.